Perfecting Equilibrium Volume Two, Issue 44

Just yesterday mornin', they let me know you were gone

Suzanne, the plans they made put an end to you

I walked out this morning and I wrote down this song

I just can't remember who to send it to

I've seen fire and I've seen rain

I've seen sunny days that I thought would never end

I've seen lonely times when I could not find a friend

But I always thought that I'd see you again

The Sunday Reader, July 30, 2023

The call, when it came, was unfortunately not a surprise. But it was still the kind of shock deep in your bones that you immediately know will be keeping you awake for many nights to come.

“This is Dallas Police Homicide. We need to talk to you as soon as possible about David Swint.”

David Swint was a difficult man. He’d be the first to tell you that. Perhaps that’s why we were so close for so long. Decades.

He played at being more difficult than he actually was. His writing alter-ego, Uncle Dave, was bleak and black and sardonic.

But the real Dave was kinder and gentler in unexpected ways. He had definitive opinions about music and literature and art, and fiercely defended them. Steely Dan was great; the Doobie Brothers were not. He once hung up on a friend who said Steely Dan never progressed, and any Steely Dan song could have come from any of their albums.

And yet when I once confessed to the rather humiliating fact that I loved Falco’s Rock Me Amadeus, a silly song by any measure, he did not pounce. Instead he explained his theory of guilty pleasures.

Music, Dave said, has the power to recall memories. So when Rock Me Amadeus played I wasn’t hearing a ridiculous 80s synth pop song. When it played I was a 25-year-old Army sergeant photojournalist racing a stick-shift battered Toyota station wagon through the sugar cane breaks from Subic Bay to Clark Air Base, a Domke bag full of Pentax cameras and lenses on the passenger seat, all the windows down because the A/C couldn’t handle the Philippine heat, Rock Me Amadeus pounding out of an AM radio over Armed Forces Radio Network, and the hope in my heart of dinner with the very pretty Pacific Stars & Stripes office manager who was my boss.

Dave being Dave, he would then of course argue about guilty pleasure eligibility. ZZ Top was good; AC/DC was only allowable as a guilty pleasure.

Dave was a 30-year-old cub reporter when I first met him. Like most cub reporters, Dave was fresh out of college. But while the others had gone to college straight from high school, Dave had spent a decade working in a hardware store.

Then he’d had enough of hardware in particular and Grayson, Kentucky, in general, and left to go be a staff writer on a publication. He got into Marshal University, got onto the college paper, became the editor, graduated, and got a job on the Waterbury (Connecticut) Republican-American.

He was happily working away on the City Desk one day when I wandered by. I’d started a Computer-Assisted Reporting and Research section, which wasn’t much of a section, since it was only me. PCs were a rarity in newsrooms in those days. The newsrooms were filled with dumb terminals slaved to the publishing system, and there were generally a couple of Apple Macs in the photo and art departments. Spreadsheets were enough to make a reporter faint.

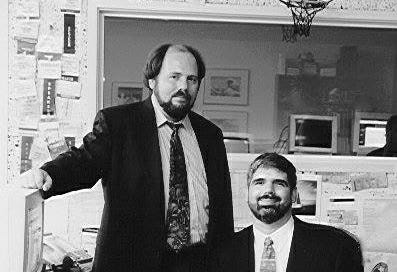

But I needed another reporter, and I hoped one of the cubs would have run across a computer or two in college. While most of the cubs were distressingly young, Dave was…well, Dave. He apparently was born into grumpy middle age, balding and bearded and built like a fire plug. No one would have blinked if he had been cast as Gimli the Dwarf’s brother in The Lord of the Rings.

Dave turned out to have an aptitude for journalism, and computers, and Computer-Assisted Reporting and Research. We did a bunch of projects together and won a stack of awards, highlighted by The Tax on Living, a deep dive into the tax system that sold out the newspaper daily for a month. The Republican-American then did a special press run of 10,000 copies of the entire series as a tabloid; those sold out too.

Dave made such a splash that a bigger paper in Ohio hired him away. I joined the American Press Institute and founded a think tank called The Media Center. This was at a time when newspapers had such a disdain for the newly emerging World Wide Web that no newsroom would allow a story to be posted online until after it had appeared in print to avoid scooping the real press.

The Media Center was founded with a grant that was supposed to cover a founding director – that was me – one API-style week-long conference, and a secretary/assistant over a two-year period.

API was a peculiar place. There was no question that conferences offered the best possible education in journalism’s best practices. But API was the sort of place that took itself a bit too seriously.

Actually, a lot too seriously. The directors dressed every day in suits and ties. Each had an assistant, always in a dress and heels. The directors had a limo take them to the Washington Correspondents Dinner every year.

Then there was the food service. Imagine the same rubbery food in chaffing dishes you’ve been served at every conference. Now picture wait staff wearing tuxedos and white gloves while watching you serve yourself from those chaffing dishes.

None of which made the food any more palatable.

My secretary/assistant slot paid more than Dave was making in Ohio, and that job hadn’t worked out as well as he had hoped. It turned out they were anxious to say they were doing computer-assisted reporting, but not so anxious to provide the computers and resources that were required to actually do it. So I called him. “I’ll come,” he said. “But I’m not wearing a dress and heels.”

We didn’t wear the suits, either. We wore black pants and black polos with the Media Center logo Dave designed stitched in red. (We had an intern program; men and women wore the same uniform.) We stretched API’s rules until they wept.

Instead of one week-long conference, we had seven working weekend workshops, and five one-day programs. These workshops blended the best and brightest newspaper people with academics, software developers, designers, folklorists, historians and more into a new media gumbo. We did the only academic quality research ever done on newspaper classified advertising. The XML schema we came up with at A Grammer for New Media became a worldwide standard.

We had merch. Dave designed coffee cups with his logo, shirts with the logo embroidered on, and more – and even our own custom-roasted coffee. Dave sold everything out. Repeatedly.

And he wrote. And wrote. The articles for the Media Center website; a novelty in 1997. The Media Center email newsletters – another novelty at that time – and their printed versions. And The Media Center research reports.

Because the wait staff didn’t work weekends, Dave ordered in a mess of food from local restaurants and had people serve themselves.

API tried to copy some of this. They started having a pizza night during conferences. They’d order in pizza, and attendees would serve themselves.

While wait staff in tuxedos and white gloves watched.

We had a big window to the corridor that let us watch people passing back and forth to another organization that had offices at the end of the hall. There was a beautiful woman who worked there who passed by several times a day. Dave would be on the phone working out logistics, or strumming a guitar…and would simply lock up mid-sentence or song every time she passed. We tried for years to get him to say anything to her – just “Hello” would have been a start – but he wouldn’t hear of it.

Like all of us, Dave was a bundle of such contradictions. He kept a guitar in our office, and would play for anyone who wandered by, or just us. He regularly hit open mike nights at bars and clubs, often playing original songs he’d written.

Dave had no compunction about getting up and playing an original song for a crowd of strangers. And yet he refused to talk to that neighbor he saw every day, or even to learn her name.

After two years at The Media Center Belo asked us to come to Texas and take all the stuff we’d been designing at The Media Center and build them for The Dallas Morning News, WFAA, the Providence Journal, KING-TV in Seattle… So we came to Dallas and got to work. Dave bought a house and settled in.

It was great for a few years. We were blazing trails into a new world. We were granted patents, and won awards. We even ended up Number 13 on the InfoWorld 100, sandwiched between IBM and Hewlett-Packard.

And David did well, but he always made it clear that this was only a temporary diversion. Once we got things up and running, he was going back to his real career – as a staff writer on a publication.

But while we were building a new world, the old one collapsed.

It was simply math. The lifeblood of newspapers was classified advertising, especially employment ads. It simply went away. The biggest buyers of employment ads were the biggest employers, who found they could just throw up a Careers tab on their website and get more applications than they could handle without paying anyone anything. US classified revenue fell from over $20 billion to under $10 billion. Media companies laid off thousands, again and again. Companies collapsed; newspapers closed. The carnage spread across all types of publications and broadcast outlets.

By 2010 there were fewer reporters than in 1940.

Creatives responded by changing, by rediscovering earlier business models. They built channels on YouTube and empires of words on Substack, working for themselves, the way Poor Richard’s publisher was…Ben Franklin.

David also changed. He became Bartleby, The Scrivner.

Now I will admit this Herman Melville short story has never made any sense to me. Not when I first read it as a teenager, and not since.

Maybe I understand it a little more, now.

The story is simple: A scrivener – basically, a law clerk – works in a Manhattan law office. One day the lawyer asks the scrivener to do something, and Bartleby replies “I would prefer not to.”

That becomes his answer to every question: requests to do his job; requests that he leave the office and stop living there.

The lawyer eventually moves the entire office away to escape; Bartleby stays. The new tenants tell him to leave; “I would prefer not to,” he replies.

David’s circle of creative friends changed with the world.

David the Scrivner said “I prefer not to.”

David was holding out for a staff writer position on a publication.

After I got off the phone with Dallas Homicide I emailed our friends to let them know he was gone. One called right away.

“I talked to him a few months ago, and he said again that he wanted a staff writer position. ‘David, there aren’t anymore,’ I told him. But he wouldn’t listen.”

Perhaps he preferred not to.

That circle of friends tried to help, for which David was alternately grateful and greatly annoyed. There were multiple GoFundMes, job leads, job referrals, offers to build a Substack for old Uncle Dave columns, offers to buy subscriptions to an Uncle Dave Substack…

And wellness calls when he posted some truly terrifying stuff.

From Dave’s LinkedIn a few months ago:

“So I got a visit from the cops yesterday. And once again, it was over something I posted online. A wellness check, making sure I wasn't diving into self-harm.

“Some folks need less free time on their hands. I express, I vent, I rant and sometimes, I even sound somewhat rational. But I try to be honest, and getting the words out there seems to help, however briefly. I need the outlet.

“My mistake is in sharing. Guess I need to knock that stuff off.”

National Geographic was perhaps the premier publication of the last half-century. It laid off all of its staff photographers a decade ago. A few weeks ago it laid off the last of its staff writers. It cannot be a coincidence David left us soon after.

Godspeed, my friend. I pray you are at peace.

Next on Perfecting Equilibrium

Tuesday August 1st-The PE Vlog: Tutorial: The AI arms race continues as Adobe adds Generative Expand

Thursday August 3rd-The PE Digest: The Week in Review and Easter Egg roundup

Friday August 4th-Foto.Feola.Friday

Thanks for writing this fitting tribute to Dave.

As I texted to the friend who forwarded it to me: I'm not really saddened by [Dave's death]. It seems so Dave. He just wasn't willing to bend to the world and I think that's kind of rare and wonderful.

His death is definitely going to give me pause for the rest of the day and maybe the weekend, but it's more of a victory for him than giving in and writing copy to sell boner pills on some stupid website would have been. It actually makes me a little proud for him that he was able to live life on his terms and thumb his nose at the rest of us and death rather than move to the middle.

Of course, after the weekend, it's back in line for me.