The End of Widespread Literacy

Walter Benjamin and Larry McMurty storytelling at the Dairy Queen

I'm a born in the country

girl they said go out and see the world

but is it bad

to want to stay

sure it's beautiful over there

but I'm not going anywhere

cuz where I stay

it's pretty great

call me crazy

but I think I’ll stay

nothing gets me like the good days

Down by the river floating away the time

open windows on the freeway

Austin is calling

South by until I die

River walking midnight

Marfa in the Moonlight

nothing beats the way I feel

when I’m under the Texas sky

The Sunday Reader, Sept. 29, 2024

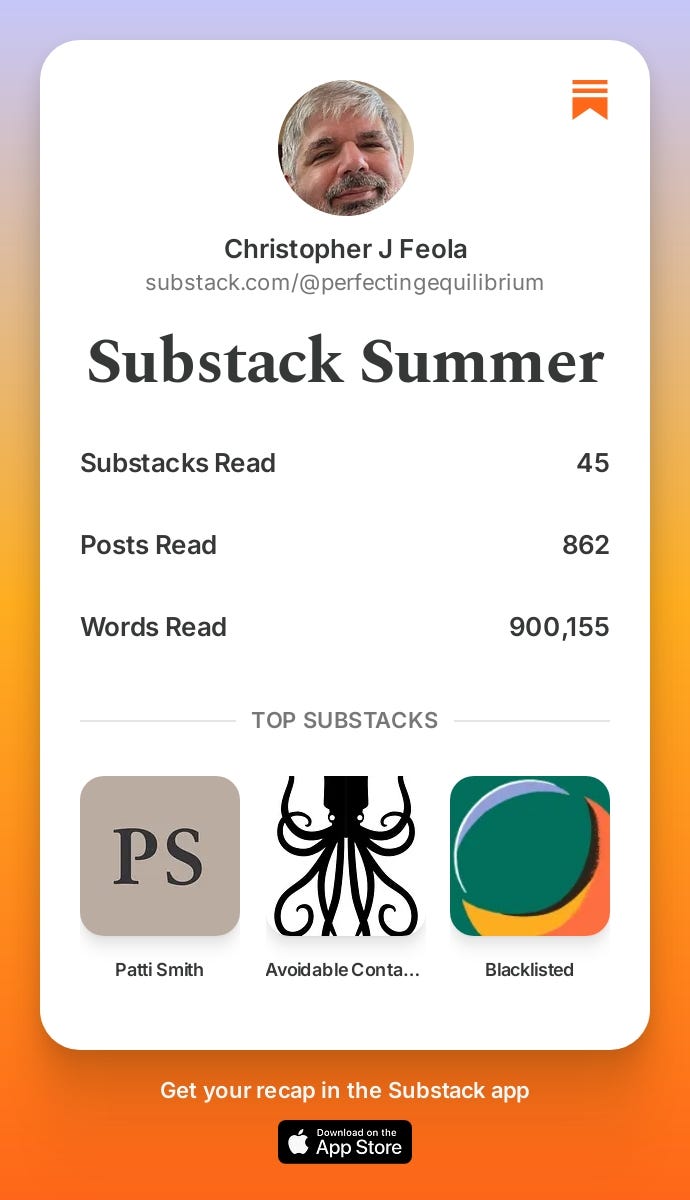

The advent of fall brought this from Substack:

Except…I have an older Substack reading address, too.

A million-word summer. Just on Substack, so not counting the dozens of books I read this summer, and lord knows how many blogs and web pages and email newsletters. So of course I immediately thought I wonder how many words I wrote?

Larry McMurtry would have understood.

Share your own Summer Recap

You can see your own summer recap in the Substack app. I’d love to see what you’ve been reading.

McMurtry is well known as the great novelist of Texas past and present, author of Lonesome Dove and The Last Picture Show, Buffalo Girls and Terms of Endearment. What is less well known is that he was also one of the world’s great antiquarian book scouts and dealers. When he moved his store Booked Up from Georgetown to his hometown of Archer City, Texas, the collection filled a third of the downtown buildings, resurrecting the dying town from The Last Picture Show.

McMurtry would have understood my reaction. He said that when he was reading he always felt he should be writing, and when he was writing he always felt he should be reading.

He did a lot of both. His antiquarian book stock approached a half-million volumes. He wrote more than 30 novels.

And he was a screenwriter, winning an Oscar for Brokeback Mountain to go with the Pulitzer he won for Lonesome Dove.

But it was his non-fiction that finally taught me how to see Texas.

Yes, in addition to all that other stuff McMurtry also knocked out 13 non-fiction books. And Feola gonna Feola, so of course I hadn’t read any of his novels or seen his movies — or movies made out of his novels — when I decided to read one of his non-fiction volumes.

It was the title that got me. Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen. First, it seemed highly unlikely that a German philosopher born in the waning days of the 19th Century would have ever dined at Dairy Queen. Really, that’s pretty unlikely for any German philosopher, no?

Second, what would a philosopher focused on media and storytelling want with a Dairy Queen?

Third…man, I wished I had written that title. So I bought the book.

In the summer of 1980, in the Archer City Dairy Queen, while nursing a lime Dr Pepper (a delicacy strictly local, unheard of even in the next Dairy Queen down the road-Olney’s, eighteen miles south-but easily, obtainable by anyone willing to buy a lime and a Dr Pepper) I opened a book called Illuminations and read Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller,” nominally a study of or reflection on the stories of Nikolay Leskov, but really (I came to feel, after several rereadings) an examination, and a profound one, of the growing obsolescence of what might be called practical memory and the consequent diminution of the power or oral narrative in our twentieth-century lives.

Benjamin’s essay, first published in 1936, the year McMurtry was born, is an elegy for the loss of the storyteller as a figure of critical importance to human civilization. His philosophy was shaped by the horrors World War I: No, this much is clear: experience’s stock has fallen and did so for a generation that underwent, from 1914 to 1918, one of the most horrific experiences in world history. Perhaps this is not as surprising as it seems. Was the observation not made at the time that people returned mute from the battlefield? They did not come back richer in experiences they could impart, but poorer.

McMurtry maps Benjamin’s theory onto the changes Archer City has undergone during his lifetime. All day the little groups in the Dairy Queen formed and reformed, like drifting clouds. I stayed put, imbibed a few more lime Dr Peppers, and reread “The Storyteller,” concluding that Walter Benjamin was undoubtedly right. Storytellers were nearly extinct, like whooping cranes, but the D.Q. was at least the right tide pool in which to observe the few that remained.

In 1980 there were just 76 whooping cranes left in the world which, while terrible, was actually quite the improvement from 1941’s low of 15 birds.

But good news! The whooping crane is doing much better — there are now around 600 birds.

And storytellers are also thriving. Just not the way Benjamin and McMurtry expected.

Indeed, my fears have always run 180 degrees in the opposite direction. It is hard to comprehend what a small portion of human history has been blessed with widespread literacy. Humans have been around for tens of thousands of years, but it’s been less than 600 years since Gutenberg invented the printing press and started humanity down the path to universal literacy.

Benjamin and McMurtry are right that by their time the supremacy of oral storytellers had been displaced by the industrialized mass production of the written word. But their time was the 20th Century at the peak of the Industrial Age.

It’s our time now, and this time is the dawning of the Information Age, and everyone is telling stories all the time. On TikTok. On Instagram. On YouTube.

Indeed, though Siri sucks and Alexa has faded away, at some point voice will work. Once computers and the Internet are fully usable with voice input and video output, whither literacy?

Think of the years students spend learning to read, and to read critically, and then to write, and then to write with passion and persuasion. I’ve been saying the same thing for two and half decades: when voice input fully matures literacy will fade away into a specialty. As many people will be able to read and write English as now can read and write Java code.

Is this a bad thing? A good thing? Certainly it will be a different way of communicating, which will change the structure of society. It’s important to remember that blind Homer’s Illiad and Odessy were oral works for hundreds of years before being written down, as was the Bible. So great art is possible without widespread literacy, and great civilizations such as Rome ruled the world long before Gutenberg’s press.

Benjamin’s point is essentially that the performance art of oral storytelling was being replaced by the planned, frozen-in-time Industrial Age construct of the novel. Which is a rather interesting concept for the novelist McMurtry to consider while sucking on yet another lime Dr Pepper at the DQ.

It’s the same age-old argument we’ve all heard measuring the value of live music versus recordings. If you have a recording of a three-minute pop song, it is always a three-minute pop song, no matter how many times you play it.

Hear that band live, however, and it may be that three-minute pop song. But tonight’s performance might also see it morph into a fascinating mashup with two other songs, and you’ll be telling fans for years that you were there and heard it live.

On the other hand, it might morph into a 30-minute jam session with a drum solo that goes on and on and on and on and on until you want to rip off your ears and hurl them at the drummer.

All of these traditions now exist together online. There are YouTubers using green screens and production tools that equal anything available in Hollywood a decade or so ago. And there are teenagers just turning their smartphone cameras on and livestreaming without any production at all.

So I think that both types of storytelling — the oral tradition and the carefully planned novel of a story — will thrive in the Information Age. I have no idea if one or the other will largely prevail, though I suspect it will be some new thing we cannot yet see.

I do think in the next decade or so we will see universal literacy start to wither away.

I guess it’s no surprise — to me, anyway, — that I did not come to McMurtry though his famous fiction. I find most serious modern fiction unreadable. I love the idea of Infinite Jest, and I’ve started it three or four times.

I still haven’t made it to Chapter Two.

This summer I did finish The Neighborhood by Noble Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, mostly by skimming the fever-dream chapters while swearing like an Army grunt — which I come to honestly — until I reached the ending, which was so contrived that for a moment I considered driving the Camaro to Peru just to smack the author. But then I reconsidered since he was also born in 1936, and smacking an 88-year-old seems unsporting.

Also, the Camaro would need new tires for a round-trip to Peru.

Likewise I’ve never made it through Don DeLillo’s 30 trillion-word description of the baseball stadium in Underworld to the playing of the actual game.

Underworld is a good example of why I read so little “serious” current fiction. My writing lodestar is Shakespeare. In all of the tens of thousands of words over 3 dozen plays, he wrote exactly one stage direction beyond Enter and Exit: Exuent, Pursued by a Bear in The Winter’s Tale.

No description of Hamlet, or Mercutio, or Juliette. No angrily or sadly or any direction at all.

Just the words. Just To Be or Not To Be; and then trust in the imagination of the reader.

I did read Lonesome Dove, and it was pretty good. But the McMurty book that really changed me was Roads, because it taught me to see Texas.

One of the things that I like about McMurtry is that he has the same sort of odd internal logic that I do. He may start someplace crazy and somewhere totally insane, but he has a logical step-be-step map for getting from Crazy Town to Insane Ally.

Roads is sort of the antimatter version of William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways, which wandered down all the small blue roads on maps and saw every inch of America. McMurtry’s conceit was that today’s interstate highway travel is the equivalent of the 19th-century river voyaging, and he wanted to see America the way they did. So he did things like flying to the Canadian border of Minnesota, renting a car, and then driving it 1,600 miles south until he ran out of America in Laredo, Texas. He crisscrosses America this way on highway after highway, without ever getting more than a mile or so from the interstate.

After all, Samuel Clemons did get off the Mississippi riverboats and go wandering around the countryside? No, he stayed with those paddle wheelers, never got much further than the docks until he became Mark Twain and left Life on the Mississippi.

McMurtry describes the countryside as he passes through it, never entirely comfortable. He feels hemmed in, claustrophobic, in the forests and mountains. Then he arrives at an ocean, and finally feels at home. The endless sky stretching to the horizons reminds him of the infinite Texas skies.

I happened to be in a 40th floor restaurant when I read this, and walked over to the window. Texas stretched out so far under the endless sky that the horizon was slightly curved, and I finally saw what was there, and how much it resembled the North Atlantic skies under which I grew up.

Thanks, Larry.

Great piece, Chris. I recommend the fine biography of McMurtry. Forgot the author, but the most recent, and maybe the only, one.