Starship Troopers Revolutionize Warfighting

Boots and armor on the ground anywhere in the world in an hour

Perfecting Equilibrium Volume Three, Issue 35

Back with my wife in Tennessee

When one day she called to me

"Virgil, quick, come and see,

There goes Robert E. Lee!"

Now, I don't mind chopping wood

And I don't care if the money's no good

You take what you need

And you leave the rest

But they should never

Have taken the very best

The Sunday Reader, March 16, 2025

The pivotal battle of the Civil War started as a shoe-shopping expedition.

By the summer of 1863 the Army of Northern Virginia was desperate for supplies, ground down by years of fighting and consistently inadequate support by the Confederate government. Shoes were in such short supply that soldiers were marching barefoot a dozen or more miles a day over hard packed roads and rough terrain.

So when Major General Henry Heth’s scouts said there was a stockpile of shoes in Gettysburg guarded only by a few militia, Heth sent his troops into the town to capture those shoes and whatever other supplies they could find.

Commanding General Robert E Lee had instructed his commanders to avoid a major battle until he could get his invading force organized and then force a decisive battle on favorable terms. But he’d also told commanders to capture supplies and disrupt Union plans. Capturing a Union supply cache would do both. So Heth ordered a reconnaissance in force.

Unfortunately for the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee was operating blind. His brilliant but impetuous cavalry commander, J.E.B. Stuart, was supposed to be screening the Army and keeping an eye on the whereabouts of the Army of the Potomac. But J.E.B. had taken his horse soldiers off on a raid.

So when Heth sent two brigades – much more than enough to handle a few militia – into Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, he didn’t realize he was actually advancing into the Army of the Potomac. By the time J.E.B. and the cavalry showed up on July 2, Lee had been forced into a fight before he was ready and with the Union holding the high ground, and the battle – and the war – were well on their way to being lost.

For shoes.

Old soldiers have a saying: Amateurs talk strategy and tactics.

Professionals talk logistics.

Now of course 21st Century warfare is a far cry from the 19th Century Civil War. But in terms of logistics, much remains the same, as was the case with the Cold War Rapid Deployment Force. The RDF’s mission was to hold a beachhead for a week, because that’s how long it would take to move the first elements of the regular Army to Europe.

This week SpaceX launched the Crew-10 mission from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

It reached Europe in 9 minutes.

SpaceX is reusing spaceships, landing them, catching rockets in chopstick contraptions. But a spaceship that lands near its launchpad can also land anywhere in the world. In an hour. Loaded with military might.

Drones and electronic warfare are changing military strategy and tactics.

Rockets will change logistics.

A look at that Rapid Deployment Force illustrates the problem of modern logistics.

After Basic Training and the Defense Information School I joined the 24th Infantry Division at Fort Stewart, GA, a high-readiness combat unit that was part of the Rapid Deployment Force.

It’s hard to remember, but in those days before the fall of the Berlin Wall there was genuine fear that the Soviet Union and the Eastern Block would break out and destroy Western Europe before anything could be done. Hence the Rapid Deployment Force: The 82nd Airborne’s job was to be on the ground in Europe fighting in 24 hours, and to last 24 hours. The 101st Air Assault was to be fighting in 48 hours, and to last 48 hours. The 24th was to join the fight in 72 hours, and last 72 hours.

All together that was six days, which was supposed to be enough time for the rest of the Army to get to Europe and join the fight. None of the Rapid Deployment Force units had a plan to hook up with the arriving main Army forces; it was assumed we would “lack unit cohesion,” which was Army Speak meaning too many of us would have been killed for there to still be organized units, so a plan for survivors was a waste of time.

The 82nd and 101st were light infantry that could head straight to Europe on regular planes. The 24th Infantry could last longer because it was mechanized, which meant it was two thirds infantry in armored personnel carriers and one third tanks. There’s enough trouble getting your carry on luggage on a regular airplane; tanks are a hard no.

So the 24th had a 10,000 foot runway at Hunter Army Airfield capable of handling Air Force C-5 Galaxy heavy lifters that could carry platoons of tanks. And the 24th had the 1/75th Ranger Battalion, the finest light infantry in the world, to parachute into enemy territory and seize an airfield for those tank-laden Galaxies to land.

Soldiers train hard; reflexively following your training is what saves you in combat. But there was no normal training for what the Rapid Deployment Force faced, being outnumbered 5-1 and struggling to slow the Soviets down long enough for the rest of the Army to join the fight.

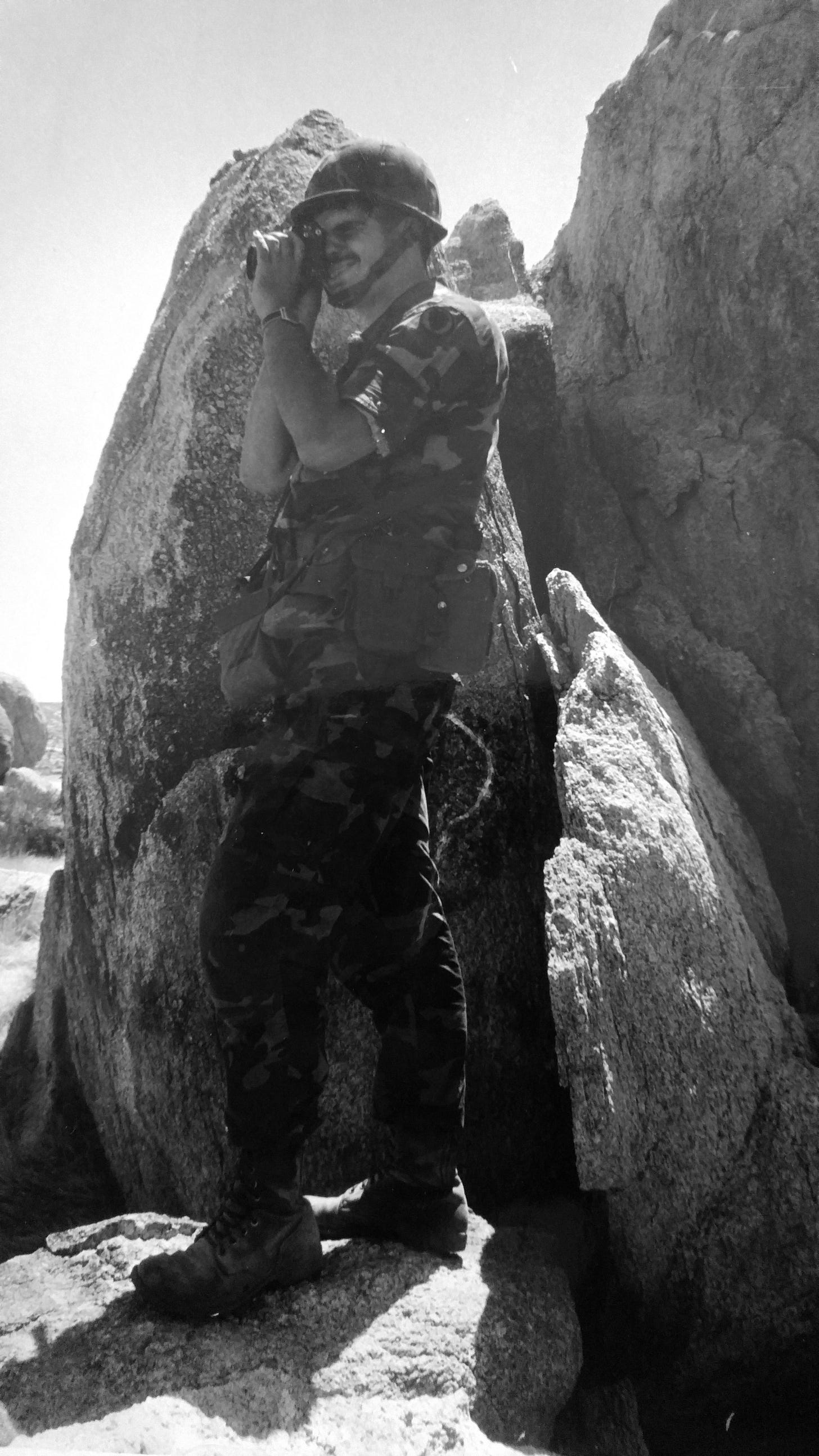

So the Army built the National Training Center in the Mojave Desert at Ft. Irwin, CA, a base larger than the state of Rhode Island, and stocked it with the OpFor. The Opposing Force wore Soviet style uniforms, marched in that high-stepping, one-armed Soviet style, and drove Soviet styled armor in waves that drowned. And we learned to hold on.

No matter how you prepared, first deployments were always a shock. The most confident of officers were reduced to babbling wrecks. “Everyone has got a plan. Until they get punched in the face,” said the great Western Philosopher Mike Tyson. Everyone had a carefully worked out battle plan until waves of OpFor rolled out of the rising sun through impenetrable smokescreens, probing for your weaknesses and then using them to destroy you.

I was deep in the desert with an infantry unit that had been wiped out. We were using the Multiple Integrated LASER Engagement System (Yes, MILES turned into LazerTag). MILES was tuned – an M16 could “kill” a soldier, but not a tank; only other tanks, missiles and the like could “kill” tanks. Once you were shot, your vest went off and you had to “sit on your hat” - helmet, as it were – and wait to be evacuated to the rear as KIA. You’d be brought back the next day as a reinforcement. For yourself. The entire company – 150 soldiers – were sitting on their hats.

This was a brigade engagement, and the colonel had a very well-developed plan for his 3,000 soldiers, tanks and armor. That plan had worked well...for about an hour, which is what it took for the OpFor the pin the brigade down, flank it, and utterly destroy it as a cohesive fighting force. The colonel was trying to order airstrikes, artillery – anything to slow the enemy. He was supposed to hold them for 12 hours; he was only going to make 4 if they drove slowly. Very slowly.

The colonel was on the radio having a complete meltdown. None of what he said is repeatable. Suffice to say it was a mix of all the swear words I knew, a surprisingly large number of ones I didn’t know, and calling out his subordinates by name and threatening anatomically improbable punishments if they failed to respond immediately.

Finally, the command sergeant major with me had heard quite enough. He got off his helmet, went to his Jeep, and clicked into the radio. “Sir!” The colonel stopped talking for the first time in forever; even senior officers listened to sergeant majors.

“No one can respond to you as we are all dead at this time.”

Everyone got annihilated at first. And my cameras filled up as everyone learned, and got better, fighting every day for five or six weeks. By the end of the training rotation, pretty much every unit was passing.

But passing did not mean winning. Passing meant you were still fighting and hadn’t been driven over like roadkill before time expired.

There was no winning in terms of driving back the OpFor, or destroying them. There was only passing; that meant being still alive and on the designated battle field and fighting when the 72 hours ended.

In those days the 24th was comprised of 16,000 soldiers, and the other two division were roughly the same size. That meant if the Army’s plan went well – and the enemy always gets a vote – it would spend the lives of almost 50,000 highly trained soldiers and tens of millions of dollars in equipment to buy six days to establish a supply line.

That’s the value of a supply line, in Lee’s day, and today.

Tomorrow will be different.

The 24th’s C5 Galaxy’s were enormous, with a maximum payload of 180,000 pounds.

SpaceX’s big rocket in current use, the Falcon Heavy, has a payload to Low Earth Orbit of 140,660 pounds. The even bigger Starship, currently in testing, can put 220,000 to 331,000 pounds in Low Earth Orbit. More than a C5.

The Pentagon has taken notice.

SpaceX has been creating new markets by driving down the price of putting cargo such as satellites into orbit. NASA’s Space Shuttle could put a kilogram of payload into orbit for $54,500.

The SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket could put that same kilogram into orbit for $2,720. The Falcon Heavy slashed that to $1,500. And the Starship is projected to cut costs further.

SpaceX is cutting payload costs by launching bigger rockets and doing it faster than everyone else. Combined. In 2024, there were 263 orbital launches worldwide. SpaceX accounted for 138, which was 95 percent of the 145 US launches for the year. China accounted for 68; no other nation reached 20.

All those launches require a lot of infrastructure, so work is underway expanding spaceports and building more. Industry leaders talk openly about having enough infrastructure to handle multiple launches a day.

The Pentagon is watching.

Here’s what they are thinking: Right now the realities of logistics mean we are spending enormous amounts of money to have forces in Germany. And Japan. And Korea.

Once we have the infrastructure for multiple launches a day, why would you do any of that? Why would you do any of that if you could deliver 300,000 pounds on a Starship anywhere in the world in an hour? Multiple times a day?

This is a bigger change to warfighting than drones and electronics. Combined.

Consider the Rapid Deployment Forces mission: Spend the lines of 50,000 soldiers retreating through Germany and France, keeping the Atlantic coast open for six days so planes and ships could start landing the main Army units.

Imagine instead Army units landing in Europe in an hour on Starships launching from the current space centers in Florida and Texas and California. Think of how military strategy and tactics will have to change if a fully equipped army can show up in an hour in your face and ready to fight.

And that’s not all. There are no front lines in missile warfare. Missiles can hit anywhere.

Now imagine a 24th Infantry Division with Starships instead of C5 Galaxies. Sure, those Starships could deliver 16,000 soldiers, their tanks, armored personnel carriers and artillery to the front lines in an hour.

But why would you do that? The oldest, most basic military wisdom is that the general who picks the battlefield – correctly – is the general that wins. That’s why Lee didn’t want the Union to pick the battlefield. When they did, and he was drawn into Gettysburg with the Union holding the high ground, he lost the battle, and the war.

So why go meet the enemy in an hour on the frontlines of a battlefield they have picked?

Why not instead point your Starships at their capital city?

Two thoughts: 1) a landing Starship is a helluva target; 2) sending an invasion force to Moscow is effectively sending a large number of big ballistic missiles to Moscow, how do you let the enemy know you are “just” invading them and not starting WW3?

It is an interesting concept of using a Starship to attack/invade another country. There would still be significant security and logistics to consider. First, you would have to secure the land and air of the landing site. Big Starship = big target. Second, loading and offloading process would have to be rapid…stationary targets are easy targets. Third, you would need logistics support to “catch” and offload a Starship in the target area. Not as easy as a helo with a small platoon to drop off. There are a lot of smart military logisticians that could figure it out. Food for thought.